In May, WSJ published The Quants (requires WSJ subscription), a series around the subject of quantitative trading.

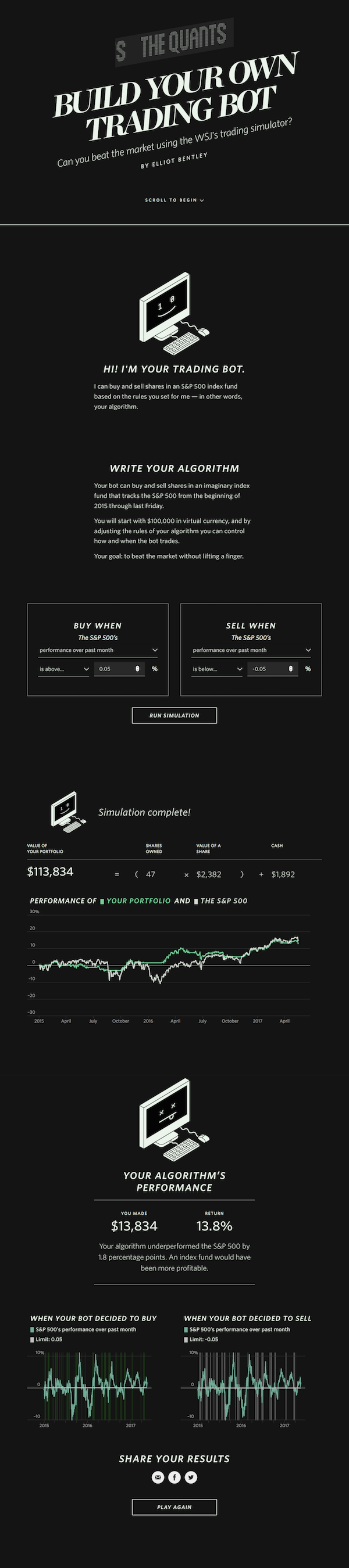

My contribution was an algorithmic trading game, Build Your Own Trading Bot (again, requires subscription), which went through multiple revisions over its four-month-ish development period.1

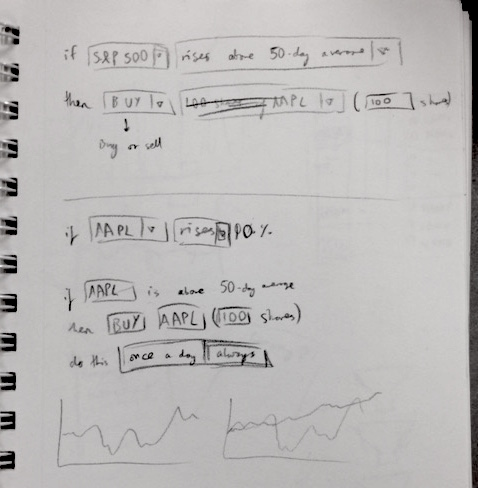

Sketching ideas

The concept behind the game was to build a simulation simple enough to be accessible and communicate the basic concepts, while still providing enough variety in trading strategies to be fun.

One inspiration for the game was Quantopian, a website that allows anyone with a bit of programming knowledge to write their own trading bots in Python, simulate them on historical and live data, and compete to have them trade with real money.

However, we wanted to assume zero programming knowledge. For a user-friendly interface to build these algorithms with, I looked to If This Then That, which provides a simple two-step interface to combine APIs of various web services.

My earliest sketches were already envisioning this “if X then Y” pattern:

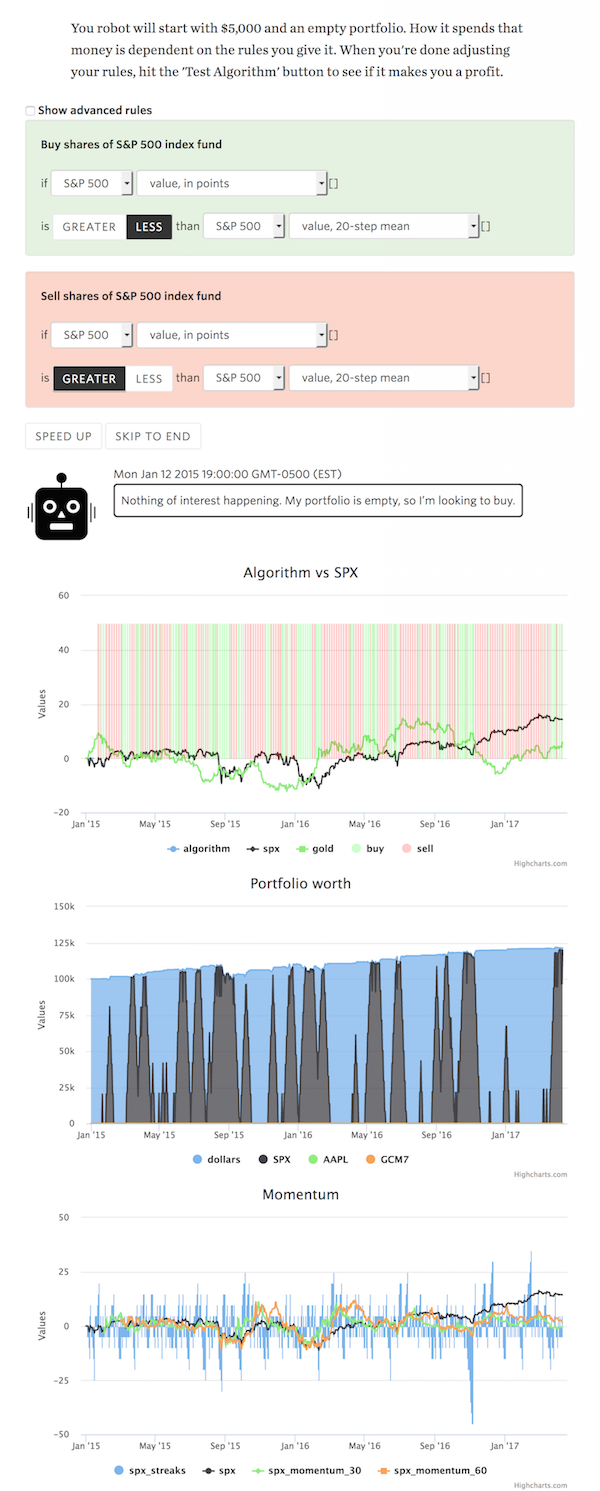

With some sketches down, I began coding a prototype. Here’s a full-length screenshot:

Once this rough proof-of-concept was complete, the real work began: working closely with my colleague Jessia Ma to polish the interface and come up with a compelling visual design.

Writing (and re-writing) the rules

Within the app, rules for when to buy and sell shares are represented as JavaScript objects:

{

"action": "Buy",

"comparison": "lessThan",

"values": [

{

"type": "figure",

"instrument": "SPX",

"measure": "value"

},

{

"type": "figure",

"instrument": "SPX",

"measure": "mean_month"

}

],

"sessions": 1,

"then": ["BUY", "SPX", 10],

"instances": 999999999999

}(The above means: Buy 10 shares of the S&P 500 index fund if the S&P 500is above its 30-day moving average)

When the simulation is run, these are converted into functions, which are then run on each (virtual) day.2 This structure allowed me to completely separate the interface from the underlying simulation.

As you can see from the object above, the simulation actually contains more features than were eventually surfaced in the game’s interface. For example, at one point it was possible to buy stocks other than the S&P 500 – although at the time, the only options were the S&P 500, gold and shares in Apple.

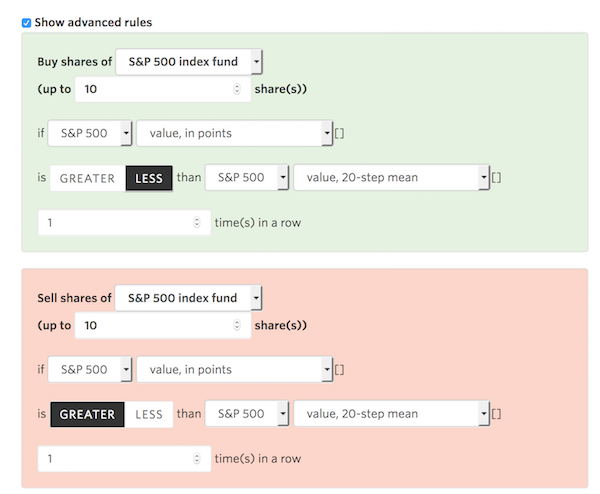

For a while, some of these features were hidden behind an “advanced” checkbox:

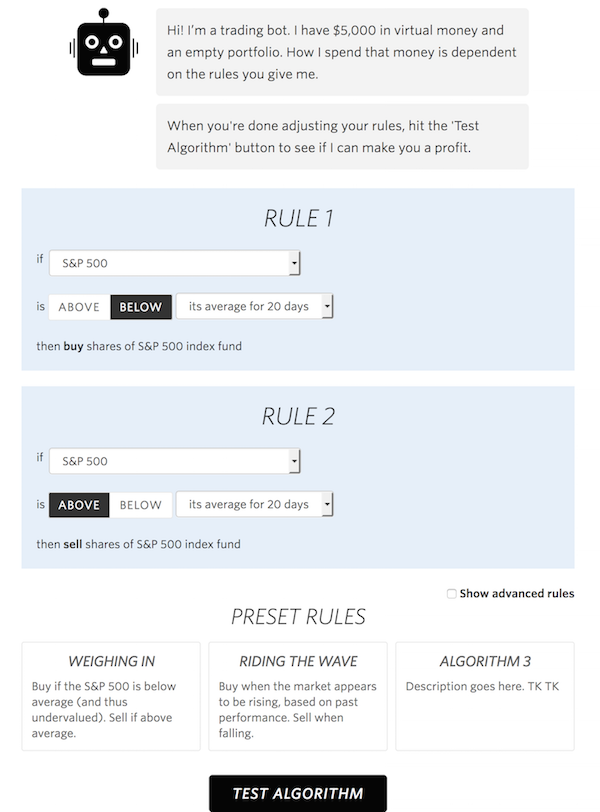

But let’s be honest, that’s an unapproachable mess. The interface was reduced to a smaller number of form inputs, and felt clearer and more approachable with each reduction.3

The preset rules at the bottom were eventually removed because they felt unnecessary and against the principle of explaining the core concepts of algorithmic trading.

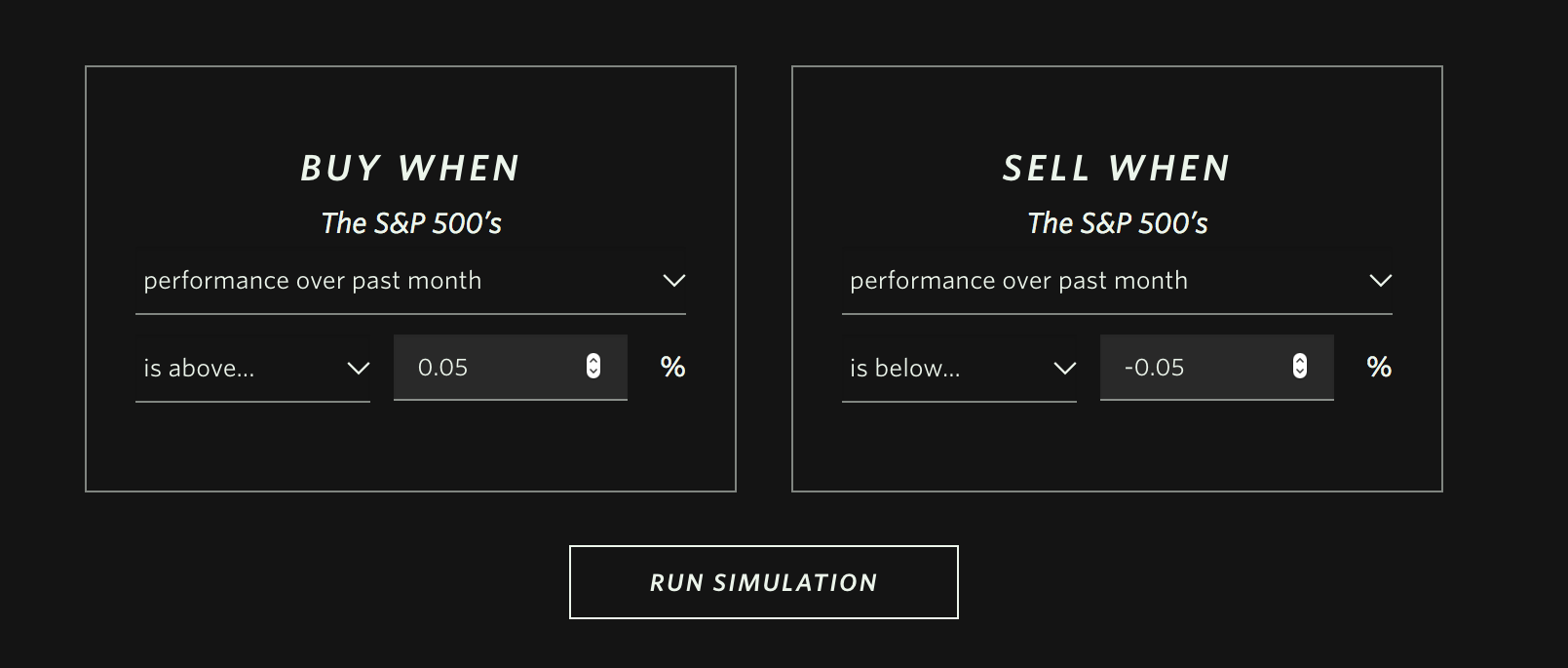

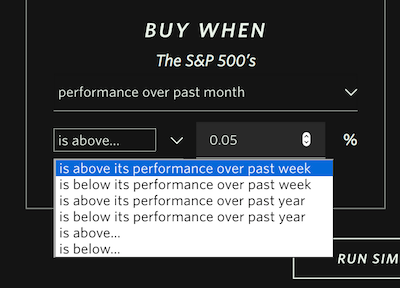

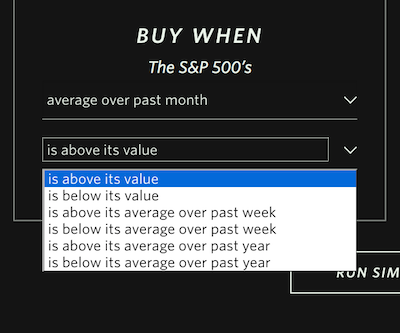

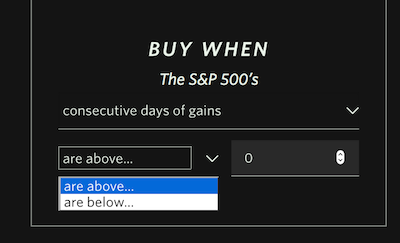

Eventually the interface for the rules was boiled down to two dropdowns per rule (plus number inputs if needed).

The contents of the second dropdown in each rule are dynamic and only include relevant comparisons, to prevent the reader from being overwhelmed with options:

This took a lot of time to get right, but learning React to write the interface helped a lot, especially when it came to last-minute debugging.

A window into bot’s mind

Another challenge was what to show once the simulation begun. Early versions had the bot announcing and explaining its decision on every tick, but this was boring when slow and unreadable when fast.

I tried making it a chatbot-style scrolling feed, but that didn’t solve the problem either.

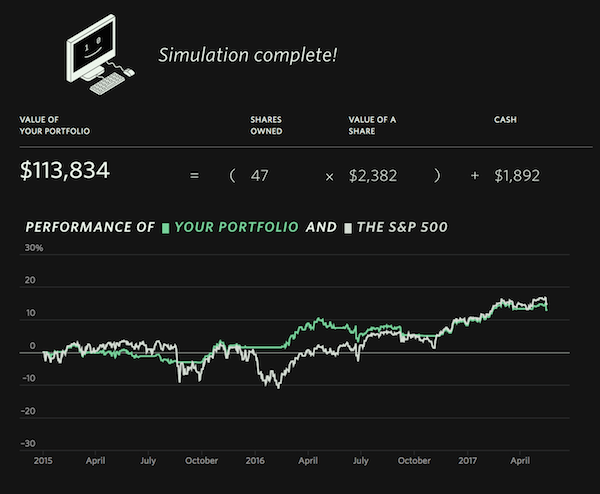

Eventually we moved to a more standard dashboard view, which has less personality but, I think, provides a better view of the simulation’s inner workings.

The addition of Jess Kuronen’s adorable illustrations certainly helped make up for any lost character.

So yeah

It was a tonne of work, but I’m pretty proud of the final piece. Here’s a full-length screenshot showing the game after a simulation has been run:

Footnotes

-

I began sketching ideas and writing code four months before publication. The actual development time was probably more like a month of full-time work. ↩

-

The simulation takes milliseconds to complete, and the ‘playback’ the reader sees is artificially slowed down. The speed of that playback was tweaked multiple times throughout development. ↩

-

The “advanced” checkbox stuck around for a while, even after a refactor disabled its functionality. Up until the last minute I was still planning on reimplementing it – until I realised it wouldn’t be missed. ↩

Published .